REVIEWS

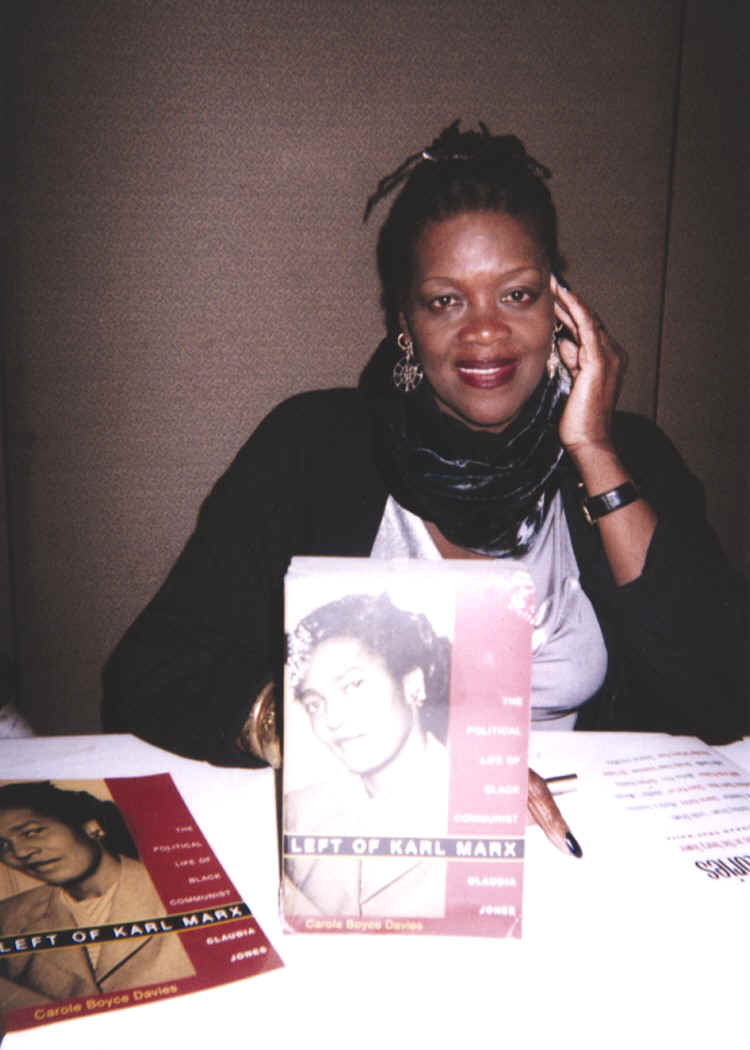

Left

Of Karl Marx

by Dr. Carole Boyce-Davies

Left of Karl Marx is essential reading for students of the broader Caribbean community. -- Linden Lewis

PDF REVIEWS

(Left of Karl Marx: The Political

Life of Black Communist Claudia Jones.

Carole Boyce Davies. Durham

and London: Duke University Press, 2008 vii+311 pp. Cloth US$ 79.95,

Paper US$22.95)

Linden Lewis - linden.lewis@bucknell.edu At the 33rd Annual

Caribbean Studies Association conference held in San Andres, Columbia last

year, I told Carole Boyce Davies that Claudia Jones is to left of Marx,

depending on where you stand in relation to the latter.

Her quick-witted reply to me was “true, so you have to stand with

Marx”. In her book Left

of Karl Marx: The Political Life of Black Communist Claudia Jones,

Davies moved beyond the physical location of Jones’ burial site, to

argue that the latter is both located in death, as she was ideologically

in life, to the left of Karl Marx. Admittedly,

this is a clever book title, but to address some lacunae in the work of

Marx does not necessarily place one to his left. To suggest a position to

the left of Marx is to assert a more radical, more extreme position,

perhaps even a dogmatic stance. Davies

is not at her most persuasive in this claim, particularly, when she is at

pains throughout the book to note Claudia Jones’ commitment to

Marxism-Leninism. Davies clearly indicates that the

book is not a work of biography but a study of one of the most important

black radical thinkers of the time. It

was good to see that Davies acknowledged her initial encounter with

Claudia Jones’ contribution to a chance audience with Buzz Johnson, who

at the time was advocating that more work needed be done on this

Trinidadian-born woman. Over

the years, Johnson’s initial effort (see, I Think of My Mother)

to rescue from obscurity, the political work and contribution of Jones has

been essentially vilified as intellectually underdeveloped. Claudia Jones in the opinion of

Carol Boyce-Davies, was a ‘sister outsider’ in the sense in which

Audre Lorde used that term. “The

fact is that she is not well know in the Caribbean, just as she is also

not remembered in the According to the FBI’s files,

Jones was “a member of the National Committee, of CP USA; Secretary of

the Women’s Commission, CP USA, and Negro affairs editor of the “Daily

Worker.” She is one of the

most prominent of the younger leading Negro Communists (cited in Davies,

p. 197). Claudia Jones was no

doubt a very important theoretician for the Communist Party of the United

States of America (CPUSA), but to argue that “if the party made Jones,

she also made it, at this time” (p. 31), is to stretch her contribution

just a bit beyond reason. In addition to her work within the

CPUSA, Jones was also a journalist of long standing not only in the United

States but also later in the United Kingdom where she settled after being

deported from the former. Some

have credited Jones with having established a radical, black, journalism

tradition in the Given Jones’ activism, her

linking of women’s rights and anti-imperialism, her opposition to Jim

Crow segregation, and her explicit communist connections, it was no

surprise that she would merit the attention of a the US government in the

heydays of the McCarthy witch hunts. Claudia

Jones was first arrested in 1948 and threatened with deportation.

She was convicted in 1953 under the Smith and McCarran-Walter Act,

and sentenced to one year and a day and fined $200.

She was imprisoned at Alderson, West Virginia.

By the time she had been released, deportation was already ordered.

She was forced to leave the only country she had know as home since she

was nine years old. Jones was

sent to London, where the according to Davies, the British authorities

felt that it might have been better to control her and her political

ideas, than in her native Trinidad. Unlike her US experience, Jones

received an unenthusiastic reception from the Communist Party of Great

Britain (CPGB). Given her

difficulties with the party, she turned her attention to addressing the

problems of immigration and racism facing the African, Asian and Caribbean

communities. She is generally

credited with establishing the Notting Hill carnival, in response to

“the riots and intimidation of Caribbean people in Notting Hill and

Nottingham and in particular to the murder of Kelso Cochrane*” (p. 178).

Jones believed: “A people’s art is the genesis of their own

freedom” (cited in Davies, p. 125).

She did not separate the political from the aesthetic.

Deportation from the U.S. therefore did not dampen Jones’

political activism; it simply broadened the scope of her work,

reconfiguring it according to the specific cultural peculiarities of

England. Carole Boyce makes an important

contribution to the history of Caribbean, communist, feminist women, such

as Hermie Huiswoud and Grace Campbell, who have tended to figure only at

the margins of their male counterparts’ political profiles.

The work is much more compelling in the chapters where Davies

discusses Claudia Jones’ deportation, carnival and Diaspora activism,

and in her work in the interest of peace.

Claudia Jones died in 1964 of heart failure in London.

There are areas of Claudia Jones’ life still in need of

exploration however. For example, Paul Robeson’s telephone call at

Jones’ funeral was no ordinary intervention, for some, it was one of the

highlights of the entire service. The

confusion surrounding the funeral arrangements and who were asked to speak

on her behalf is an interesting story in its own right. The attempt to

bury her quickly by the CPGB is another story of intrigue.

However the clash between the CPGB’s atheistic orientation to

such matters and the desire to have an appropriate religiously oriented

service, complete with church hymns selected by the Caribbean community of

which she had been a significant part, and who related to her in quite

different political terms, all need to be aired fully in a future

biography of Claudia Jones. Left

of Karl Marx is essential reading for students of the broader Caribbean

community.

Department of Sociology &

Anthropology

Bucknell University, Pennsylvania